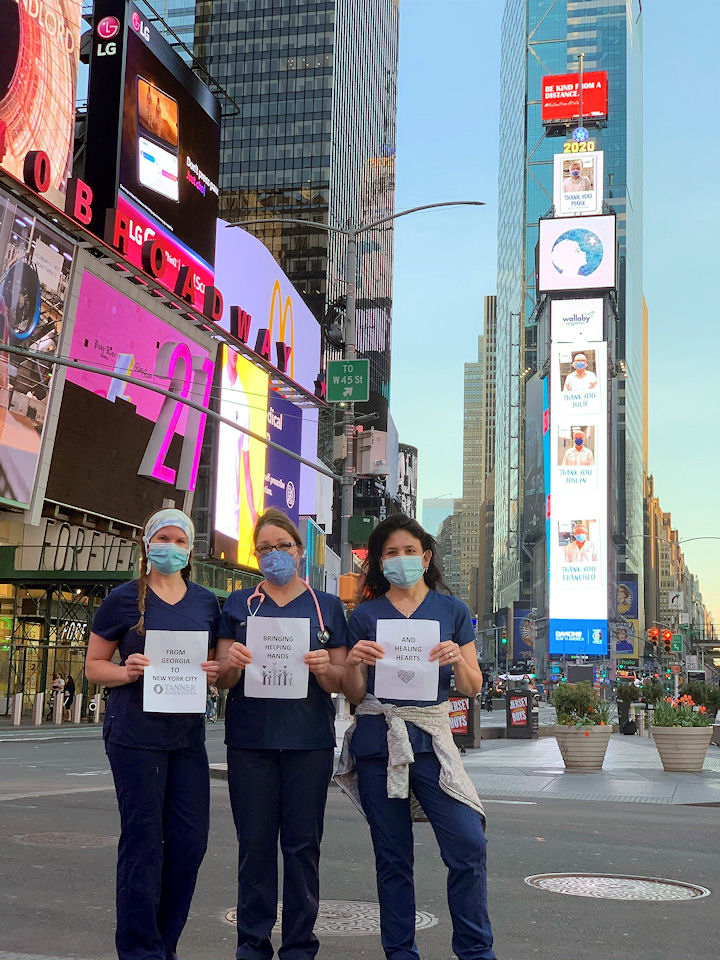

When you think of New York City, images of bright lights, elaborate window displays and a people-filled Times Square probably come to mind. For three nurses from Tanner Health System, their recent relief trip to the Big Apple took them far away from the glitz and glamour of the big city to the bedsides of sick COVID-19 patients in some of the largest, busiest and grittiest hospitals in the country and in the fight against the novel virus.

The plight of New York City during this pandemic has been well-documented. Daily national news reports detail the grim statistics and challenges facing patients and healthcare workers on the front lines as well as government officials grappling with the response.

When Governor Andrew Cuomo issued a public plea in early April for available healthcare workers to come to New York City to help, Tanner’s Joy Horton, RN, Higgins General Hospital in Bremen; Gina Robertson, RN, Tanner Medical Center/Carrollton; and Emilee Barron, RN, West Georgia Center for Plastic Surgery, were listening – and quickly, collectively agreed they wanted to help and they wanted to do it together.

None of them had participated in a relief effort like this before or been to New York City. Robertson took the lead and, after a six-hour marathon of telephone redials, finally got through, provided their credentials as RNs and arranged for all three to join the relief effort.

Reporting for duty in the Big Apple

Within 48 hours, the trio landed in New York and reported for duty along with 400 other recruits from across the country just that day alone. The emergency staffing firm, which coordinated travel, food, housing and scheduling for emergency health care providers, struggled to process the overwhelming response and make hospital and shift assignments.

Three days later, they received their shift assignments at three different hospitals in the city. Both Robertson and Barron were assigned to the emergency departments (ED) of Queens Hospital Center and Harlem Hospital, respectively. Horton went to work in the ED of Jacobi Medical Center and as a floater in the intensive care unit (ICU) and the post-anesthesia care unit there.

Working different shifts and hospitals, the three saw each other only occasionally during the approximately four weeks they were in New York City. But their experiences were similar and validated the widespread news reports that revealed a healthcare system overrun by sick and dying patients – a fear shared by hospital systems across the country, including Tanner. All three expressed renewed appreciation for the standards of care, nurse patient ratios, accountability and other quality and patient engagement practices at Tanner following their emergency assignments.

Nurses, PPE and critical meds were in short supply

Nurses were in short supply across the city due to the high numbers of sick patients, sick medical staff and the pre-pandemic nurse patient ratios which, according to Horton, equaled about 10 to 15 patients per nurse. In one hospital ED, the staffing equaled Tanner’s but for 30-40 rooms with double occupancy and, on some particularly tough days, up to six patients in a room.

According to Robertson, about 90% of the nurses there were either emergency staffing or military while the few incumbent – and well – nurses served as leads. Many of the mid-level professionals assisting in care were either still in training or right out of school. Care protocols were limited, if they existed at all.

“It was like a war zone,” Robertson added.

Unlike Tanner’s pre-emptive care practices which start help right away for patients, said Barron, the nurses in New York EDs were instructed not to start intravenous therapy, draw blood, etc. until after a doctor assessed the patient.

“It was a very different experience,” said Horton. “I am sure my mouth dropped open in shock several times on my first day there. I am so thankful for Tanner’s standards of care and I wanted to hug all the people who set those up when I got back home to Georgia. I will never again take that for granted.”

Initially, medical staff was instructed not to wear face masks out of concern they would offend patients. All personal protective equipment (PPE) was in short supply.

“It’s also virtually impossible to don and doff PPE properly when you have 15 patients,” said Barron.

Critical drug supplies were also depleted, and staff did their own calls and leg work, like contacting the pharmacy or lab to provide care for their patients.

Due to the diverse patient population and visitor restrictions typical in all hospitals at the time, medical staff relied on the telephone-based “language lines” at least three to four times daily to communicate with patients and, where possible, family members trying to check on their loved ones. Many patients were homeless, indigent and hungry, they said, and their medical issues were often more complex.

“We knew many of them would not make it,” said Horton.

Horton described the patients she cared for in New York as “appreciative, thankful, precious people. They were so grateful for the compassion and care – and sometimes just a kind word, someone to talk with.”

That compassion and concern extended to the New York City-based medical staff, the three agreed.

“The staff members were sick themselves and they had to leave work to recover. God opened every single door to get me there, and I am so thankful,” said Robertson. “Health care is very much like the military. We stick together no matter where we serve. We had people down and we needed to be there to take care of patients.”

There were also moments of joy during those long, 12-hour shifts. Robertson recalls the patient they were able to keep alive for five hours so that his children could say good bye.

Barron remembers a woman who had already attempted to get behavioral health support at three different city EDs and had been turned away – her husband had passed away from COVID-19.

“She was an emotional wreck. She lost her husband, and she didn’t get to say goodbye, and had no other family. She needed human contact,” said Barron.

During the relief effort, new friendships developed with caregivers from other healthcare organizations – relationships the trio expect will last a lifetime.

Back home in Georgia and grateful

Back home in Georgia now, all three are either already back at work at Tanner or preparing to return, following proper quarantining.

Tanner colleagues texted throughout their New York trip to ensure they were okay and to ask if things were as tough as the TV reports indicated. It was, they confirmed.

“I will never again take for granted where I am from or the people I work with. Our doctors sit down with patients and families. They care. The personal touch and great bedside manner of all of our Tanner care givers does matter,” said Robertson.

They’re ready to answer the call again, too, when the need arises.